ou can download the application used in this article.

The latest version is GSA_ver_1_7_64S, updated on December 13.

For detailed instructions on how to use it, please refer to:

“GPT-ScoreAID: An Application for Scoring and Feedback on Descriptive Answers.”

👉 Download it here!

👉Contact the Author ! (2025/12/30)

Introduction

On June 30, 2025, Google announced that it would provide free access to Gemini in Classroom—an educational version of its generative AI tool—through Google Workspace for Education, which is already widely used in U.S. schools. According to the announcement, the tool includes more than 30 new features, such as creating lesson plan outlines, simple tests, and rubrics. Then, on August 8, the latest version of ChatGPT-5, was released. Clearly, generative AI continues to advance at an accelerating pace this year.

On the other hand, there are also negative developments. News reports in the United States indicate that, due to the impact of generative AI, many young university graduates are facing a situation reminiscent of the “employment ice age.” In particular, talented individuals in the ICT sector are struggling to find suitable positions.

I myself teach part-time at a university of education, where I am responsible for methods of mathematics education. Among the teaching methodology courses, how to write a lesson plan is always one of the required topics. Yet, looking only a few years ahead, it is likely that schools will have an environment where generative AI routinely supports teachers’ work: if you specify the unit or content you wish to teach, AI will generate the lesson plan for you. This raises a serious question that struck me this summer: Do we really need to train student teachers to master the skill of writing lesson plans on their own?

The reality is that schools cannot afford to delay their response to generative AI. As Alvin Toffler once put it, the world of education is like “an old jalopy moving at 10 km/h on a superhighway with a speed limit of 100 km/h” (Revolutionary Wealth, 2006). Many teachers’ rooms still give the impression of being slow to take the first step. With this in mind, this paper explores how schools might approach in-house training on generative AI, and from what perspectives such training should be conducted.

60-Minute Crash Course: Generative AI for Teachers

At research schools or hub schools within a district, it is often possible to secure sufficient time for in-school professional development, with structures in place to support training. However, in many schools, due in part to work-style reforms, the reality is that opportunities for training are scarce—even holding a session once a month is becoming increasingly difficult. Moreover, the duration of a single training session is usually no more than 60 minutes, including time for questions and discussion.

Given these constraints, I began considering: What kind of training on generative AI can realistically be conducted within a 60-minute in-school workshop?

Example Slide Deck for a 60-Minute In-School Training

- Future Classroom Pilot Projects

- Will This Really Be the Future?

- What Is Generative AI?

- An Image of a Chihuahua Walking with a Guitar

- Types of Generative AI

- Getting Started with ChatGPT

- Writing and Summarizing Text with AI

- Using AI to Draft a Class Newsletter

- Practical Applications of AI in Writing

- Analyzing Survey Responses

- PTA Survey: “Are You for or Against Overnight Trips?”

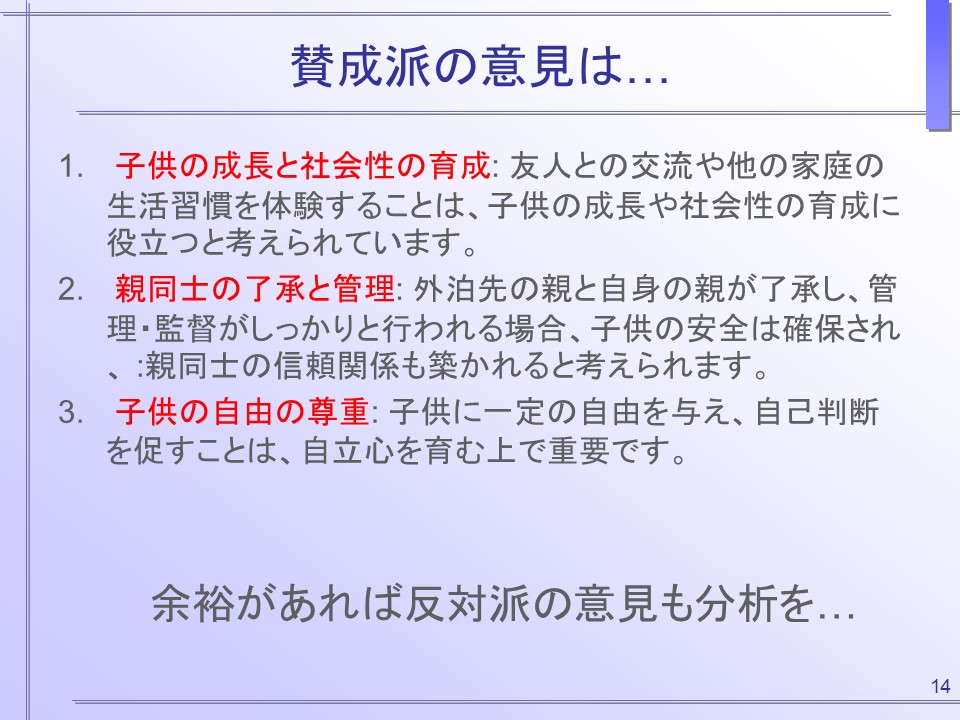

- Voices from the Pro Side…

- Generative AI Excels at Writing and Analysis

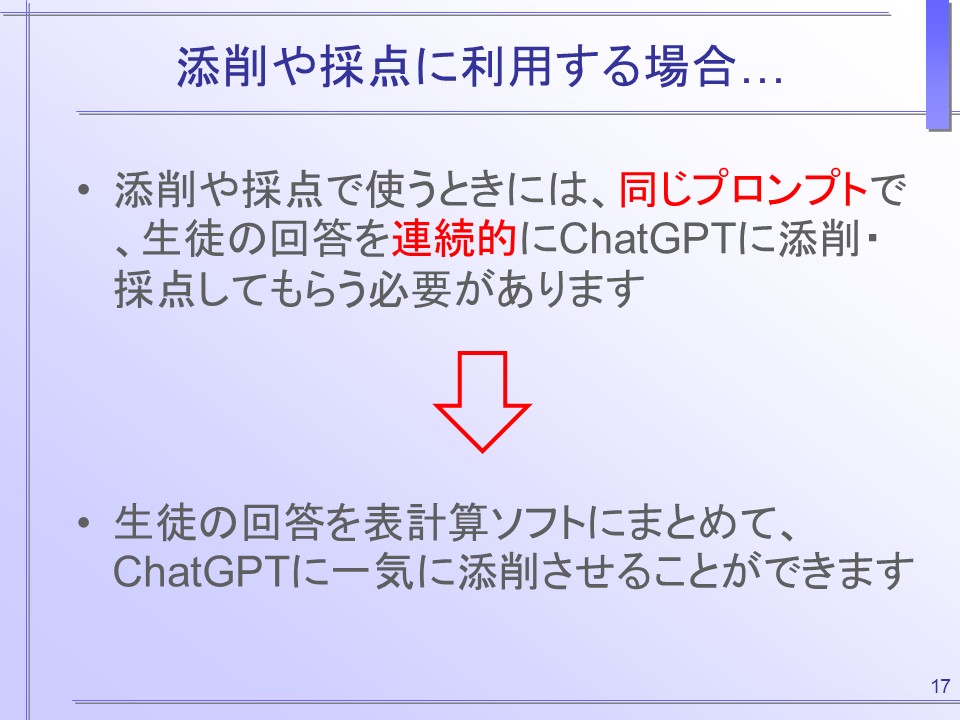

- Grading and Giving Feedback on Student Work

- Considerations When Using AI for Grading

- Moral Education: “I Will Become a Cleaning Professional” (Japanese text)

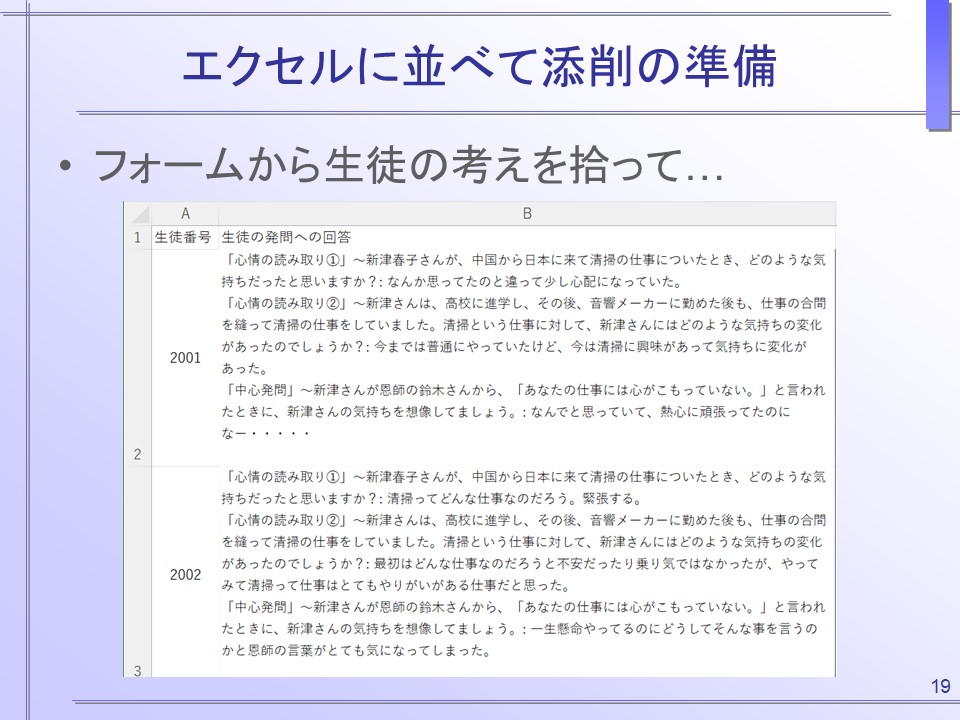

- Preparing for Feedback with Excel

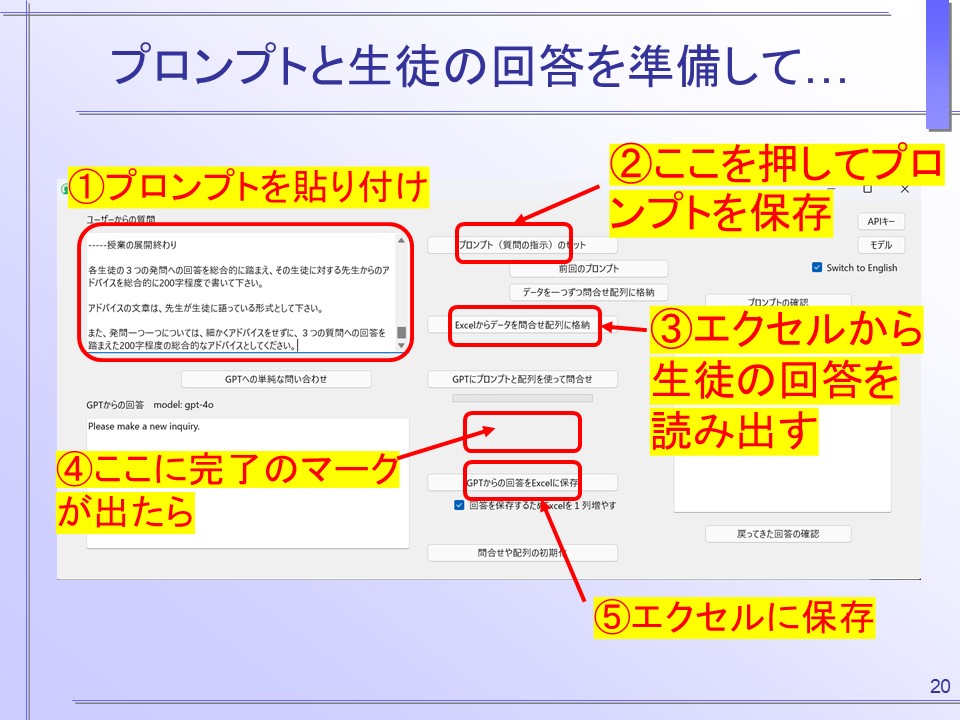

- Setting Up Prompts and Student Responses

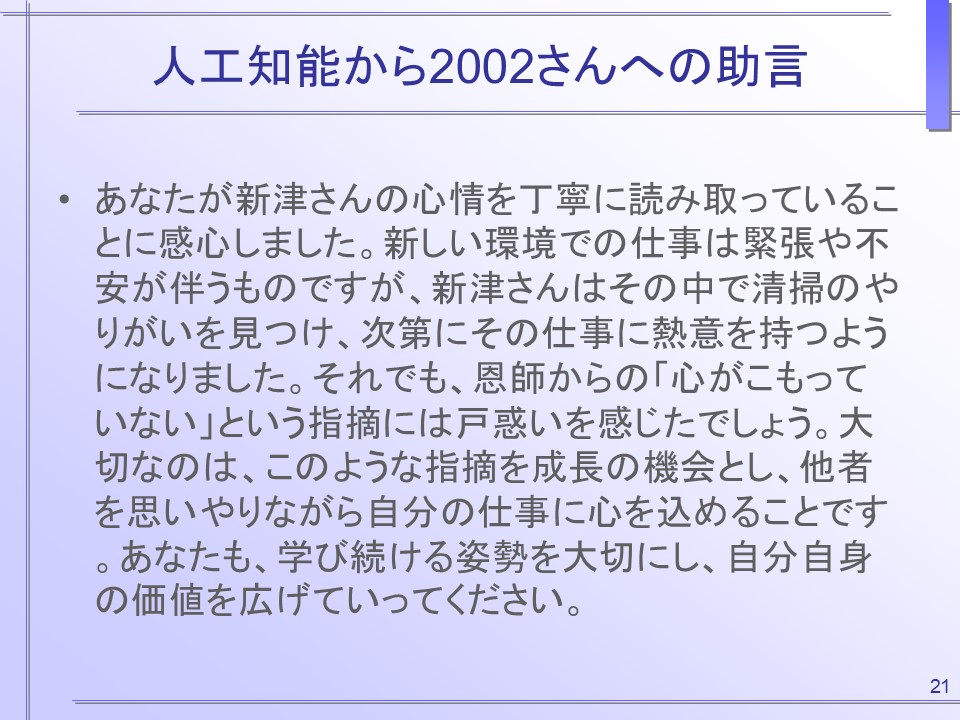

- AI Advice for Student No. 2002

- GPT-ScoreAID

- Using Generative AI with Speech Input

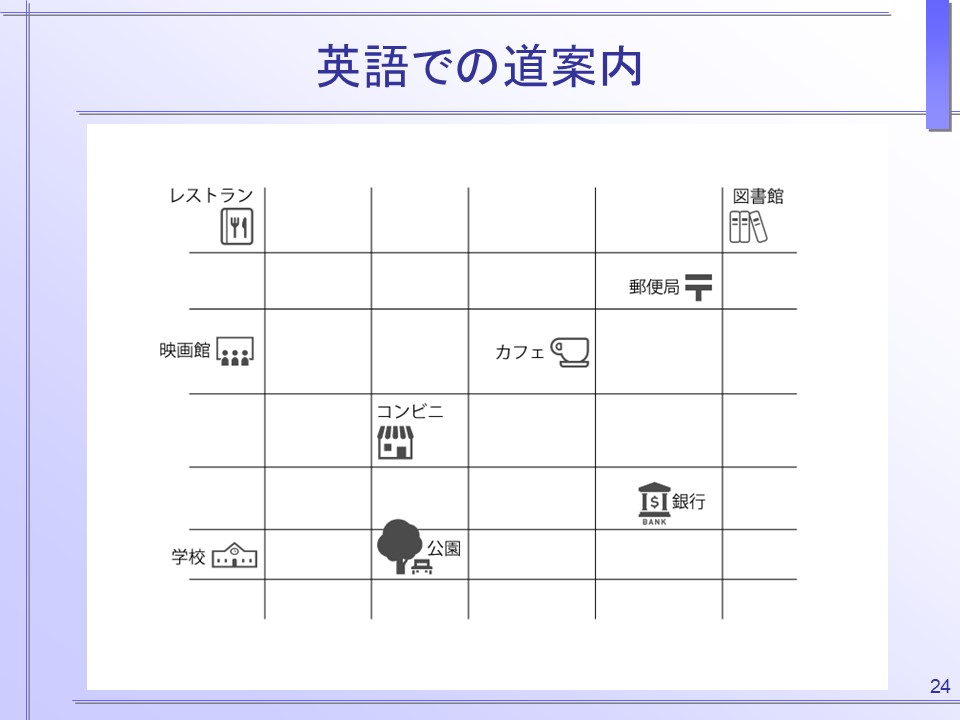

- Giving Directions in English

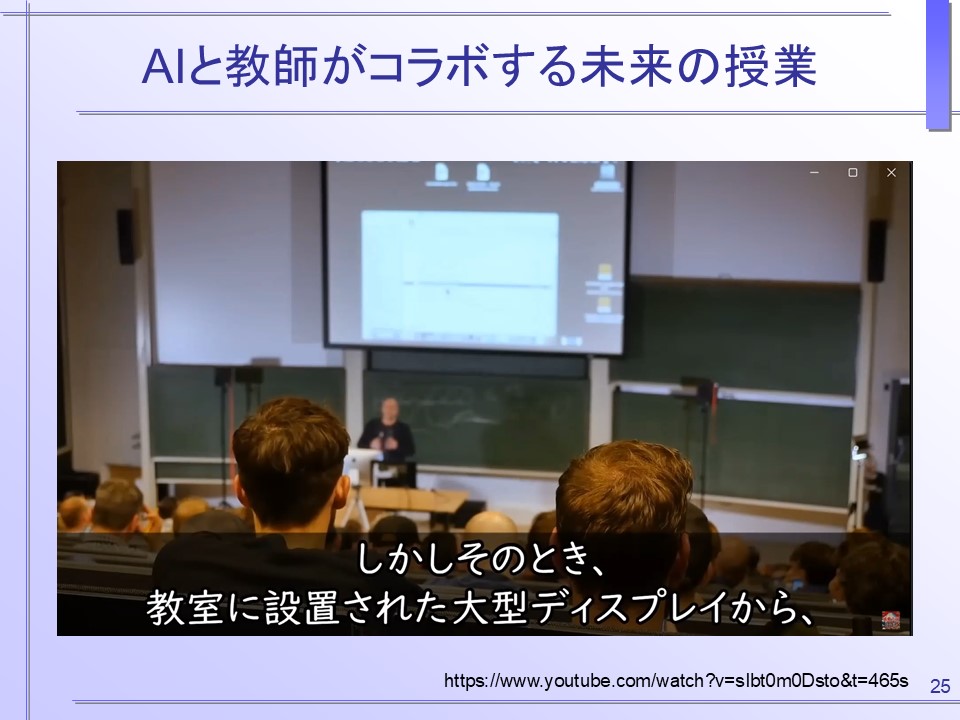

- The Future of Lessons: AI–Teacher Collaboration

- Wrap-Up of Today’s Training

- Key Points to Keep in Mind

Kicking Off the Training

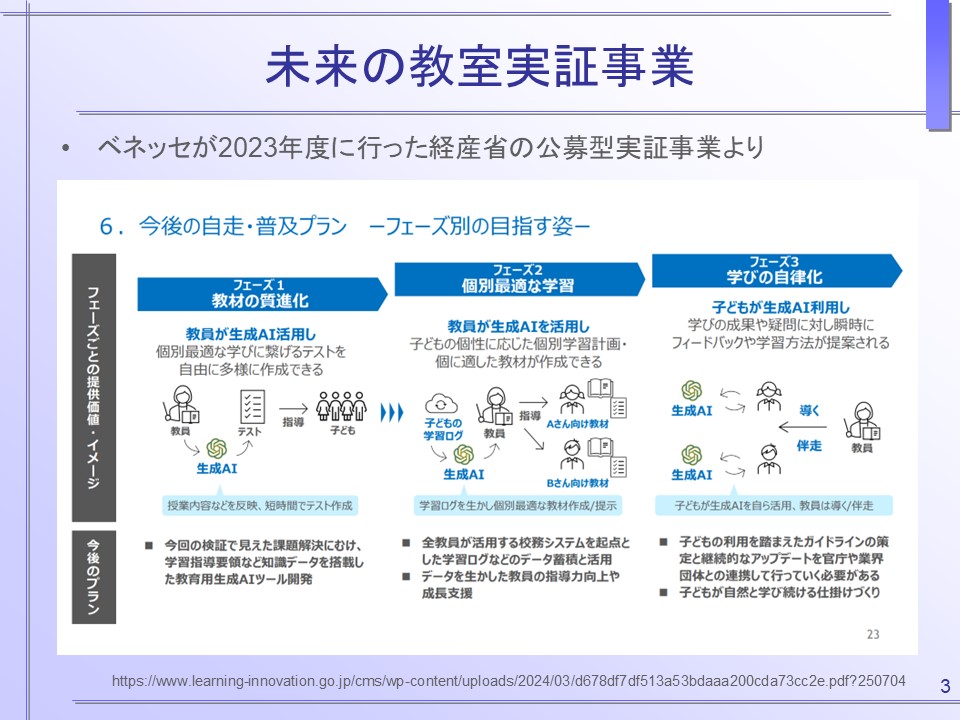

In this training example, we began by introducing a prior initiative, the Future Classroom Pilot Project, and sharing some current predictions about how schools might change with the use of generative AI (Slides 01–02). Yet, for many teachers, there was still a sense of skepticism—“Will things really change that much?”

To bridge that gap, we next demonstrated what generative AI actually is. Taking requests on the spot, we had the AI generate an image based on a prompt—this time: “a Chihuahua walking with a guitar”. At that moment, many teachers seemed to respond with, “Oh… so it can really do this!” (Slides 03–04).

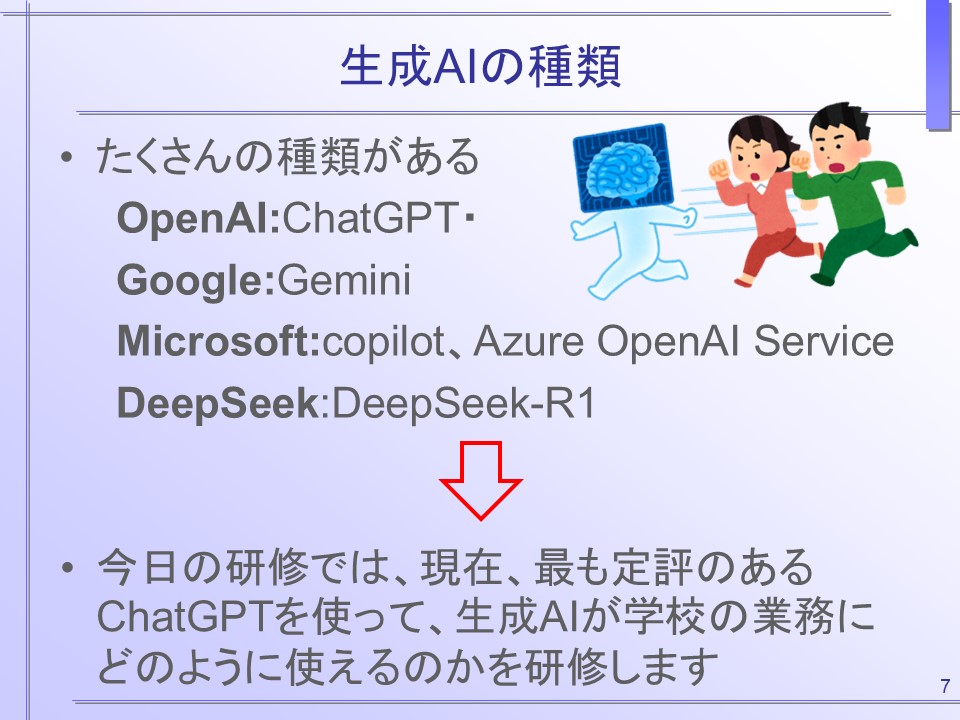

Once the atmosphere had lightened, we moved on to discuss the types of generative AI and how they are used (Slides 05–06). Since more and more teachers are already experimenting with AI in their own practice, we encouraged them to share their experiences openly. This helped everyone realize that AI comes in many forms, that versions are updated daily, and that the field continues to evolve rapidly.

The next step was hands-on practice. Because generative AI excels at producing text, we chose the scenario of creating a class newsletter. Teachers tried out the AI themselves to draft a newsletter (Slides 07–09). Some were surprised at how fluent and natural the generated writing was, while others compared their results with neighbors and marveled at the variety in the outputs.

Generative AI is also very good at summarizing large amounts of text and organizing ideas from multiple perspectives. In the second exercise, teachers worked on analyzing a parent survey filled with numerous comments, condensing them into three major points (Slides 10–13). This demonstrated how AI can also be applied effectively to administrative tasks such as survey analysis.

Through these exercises, we aimed to show teachers that using generative AI is not particularly difficult—that it is approachable and practical once you try it.

For these activities, we did not rely on the standard browser-based version of ChatGPT. Instead, we prepared an application-based tool using API keys. While free browser versions have improved in quality, they often respond slowly during peak hours, impose daily usage limits, and sometimes use slightly outdated models. To help teachers experience the full potential of state-of-the-art generative AI in school work, we wanted them to try ChatGPT with the GPT-4o model through the API.

We prepared the application provided by HemulGM on GitHub and created API keys under my account for the number of teachers participating in the training. Unlike using ChatGPT through the browser, where certain limits apply, accessing it via the API incurs usage-based charges but removes restrictions on usage frequency and model choice. This allows for a much smoother and more responsive interaction with ChatGPT.

Many teachers already pay a flat monthly subscription for ChatGPT. However, switching to API-based usage can sometimes lower costs, since you only pay for what you actually use. Heavy users may prefer the subscription model, while occasional users might find the pay-as-you-go API approach more cost-effective. We also shared this point with participants during the training session.

Where Generative AI Truly Shines: Handling Open-Ended Responses

The most impressive capability of generative AI is not in multiple-choice grading or short tasks—it is in assessing open-ended responses and working with longer pieces of writing. Even essays of 1,000 or 2,000 characters pose no difficulty: the AI can summarize them clearly and concisely. What is more striking is that, when given evaluation criteria—say, a five-level scale of A, B, C, D, E—the AI can not only assign a grade but also explain why a particular response deserves a “C.”

To help teachers grasp this transformative potential, the training included demonstrations of grading open-ended social studies questions, providing feedback on English compositions, and even commenting on student reflections collected in moral education classes—an area where AI was once thought to be almost unusable (Slides 14–20).

One of the practical challenges here is that with a single prompt (essentially, the instructions telling AI how to read and grade responses), you need to feed in all 30 students’ answers one by one. When using the browser version of ChatGPT, this quickly becomes a bottleneck.

To address this, we introduced an application called GPT-ScoreAID, which allows teachers to process all 30 students’ responses in one go using a single prompt. Teachers could then review the AI-generated feedback in detail (Slides 20 & 22).

This showcased how generative AI, when used through dedicated applications, can go far beyond simple “chat.” It enables powerful batch processing—such as evaluating an entire class at once with consistent criteria. Looking ahead, I believe this capability holds great promise for transforming aspects of school practice that were previously considered impossible to improve.

Using Voice in Educational Activities

Among the newest capabilities of generative AI, perhaps the one with the greatest potential impact on schools is its use of voice rather than text. Since the beginning of this year, both Gemini and ChatGPT have made it increasingly easy to ask questions and receive responses through spoken conversation.

In this training plan, we demonstrated this feature by having a teacher practice giving directions in English through a live voice interaction with the AI. This activity then led into a group discussion on new ways such technology could be applied in the classroom (Slides 21–22).

Voice-based AI usage opens up even more possibilities than text-based interaction. Beyond English conversation practice, teachers imagined scenarios such as having the AI act as a “virtual student” participating in a moral education lesson, or serving as a student role-play partner for young teachers who want to simulate their lesson ideas. These discussions highlighted the exciting potential of voice-based AI as a dynamic classroom participant, not just a tool.

Lessons of the Future: Coexisting with AI

It is difficult to predict exactly what role generative AI—still evolving and developing day by day—will play in the classroom of the future. Yet, even as the technology advances, our current practices need clear direction.

That is why, at the end of the training, we explored the theme of “Future Lessons Where AI and Teachers Collaborate.” As part of this, I introduced a seven-minute video (Slide 23) that I found on YouTube. Among the many examples available, this particular one resonated most strongly with my own vision of future classrooms. It depicted a debate in a U.S. university religion course where generative AI had been introduced on a trial basis as a classroom support tool. The AI listened to the discussion, pointed out inaccuracies, and even provided relevant visual materials to deepen learning. In that context, there was a striking moment when the AI itself responded, “No, I disagree! Japan should not be required to study Christianity.” The way AI was positioned in this lesson was remarkable, offering a glimpse of what the future of education could look like.

Of course, since I could not confirm the identities of the professor featured in the video or the system developed by the company, there is also a possibility that the video itself was a fabrication. In reality, the introduction and use of AI in schools may take different forms. Still, as we shape today’s practices, it is essential to reflect on how we imagine the future, and to be conscious of the direction we want to pursue.

If there is even a little extra time in an in-school training session, I would prefer to spend it sharing visions of the future and uniting staff around a common sense of purpose—rather than simply cramming in one more technical skill. After all, inspiring a shared vision may be the most powerful step toward preparing for AI-supported education.

Concluding the Training

We have now completed a 60-minute crash course on generative AI. To wrap up, I prepared two final slides (Slides 24–25). In developing this training plan, I realized once again that behind the enthusiasm and excitement of “let’s dive in!” there are also a number of important cautions to keep in mind. The last slide, “Key Points to Note,” highlights several issues that deserve particular attention at this stage.

Generative AI is a tool of unprecedented power—something humanity has never before experienced. In using it, we must approach with imagination and foresight, doing everything possible to prevent problems from arising, and ensuring we are ready to respond appropriately should issues occur.

It is worth noting that in Western countries, there have already been cases where AI-related incidents have involved matters of life and death. Keeping this in mind, I strongly encourage schools to build the right consensus within their own communities about how generative AI should be used responsibly and safely.

Toshiyuki Okuzaki

Department of Business Information,

Hakodate Otani College

コメントを残す